MUSINGS FROM THE OTHERWORLD

My current writings and musings on Celtic feminine mysticism and soulful living now find their home on Substack. I invite you to join me there but I’ve also preserved an archive of my previous writings (2021-2023) below.

Strange Solstice Seeds

The last time I wrote to you, I was writing winter letters to my grandmother who is long passed, now I’m writing love letters to the universe in the form of strange seeds.

“The making of soul-stuff calls for dreaming, fantasying, imagining. To live psychologically means to imagine things; to be in touch with soul means to live in sensuous connection with fantasy.”

James Hillman

The last time I wrote to you, I was writing winter letters to my grandmother who is long passed, now I’m writing love letters to the universe in the form of strange seeds.

As we build towards Samhain’s climax at the Winter Solstice, we enter the dreaming time, the longest night of the year here in the northern hemisphere. This week, in the Áes Dána Incubator, inspired by Yumi Sakugawa’s numinous companion, ‘Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe’, we planted some strange seeds in little pots filled with dark soil.

We then journeyed to meet the Spéirbhean, the “Sky Woman”, an Irish goddess archetype who traditionally held our aislingí, our dreams and visions. We released into a grail of tears our dreams not yet lived, and the dreams of our ancestors that they never got to live in their lifetimes. Inviting the Spéirbhean to become a patroness for our strange seeds. Some we hope will sprout in time for Imbolc and perhaps come into full bloom by the Summer Solstice, other seeds will have their own timelines, their own agendas that only retrospect can show us.

As Yumi encourages, we will send our strange seeds telepathic messages to help them grow and chant the song of the Sky Woman:

“Is mise aislingeach m'aislinge féin,

I am the dreamer of my own dreams.

Tá muinín agam as m'aislingí,

I trust in my dreams.”

What strange seeds might you plant in the dark soil of this dreaming season?

Upcoming Offerings

Voices of Celtic Wisdom is a four-month course is intended to be a deep and rich exploration of ‘Celtic’ ways and culture across Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, providing nutrients to feed your own sense of connection and belonging. It features:

19 Workshops with Guest Teachers (including myself teaching about the Celtic Otherworld)

3 Crafting Classes with wonderful Craft Teachers

A beautiful bundle posted to you with specially gathered materials from Scotland, England and Ireland for making your crafts

1 Live Sound Journey

3 Community Calls with founders Hanna Leigh and Lana Lanaia

A moderated community-sharing forum (not Facebook)

Looking to 2024

As we close 2023, I feel an acute awareness of how this year has felt like one long Samhain for me. Last January, I had a year-ahead reading with my wonderful friend Regina de Búrca of the Irish Rider Waite Tarot where the Four of Swords emerged as my card for the year, so no surprises there! I did as Clarissa Pinkola Estés urges and:

“Go out in the woods, go out. If you don’t go out in the woods nothing will ever happen and your life will never begin.”

Life has brought me on many winding trails into the shadowlands over the years. Once we reemerge back out of the woods for a time, our daimon, our soul’s guide, grows restless, eager to hoodwink us into the next phase of our becoming, and back in we go.

In I went in 2023 and back out again I am coming in 2024.

I feel that the next phase of my becoming is in Brigid’s hands. I created this image yesterday inspired by the art of John Everett Millais and Ella Young’s poetry of Brigid as Venus, our morning and evening star, our flame of delight!

She is fanning the flame within me and I will return to you early in 2024 with what I hope will be an enchanting new offering for you all.

In the meantime, I leave you with love, grá, gratitude, buíochas, and importantly, peace, síocháin.

For Peace

As the horror and brutality of war rages on in Gaza, I’ll end here with this poem, ‘For Peace’ by Irish poet and philosopher, John O’Donohue.

As the fever of day calms towards twilight,

May all that is strained in us come to ease.

May we pray for all who suffered violence today,

May an unexpected serenity surprise them.

For those who risk their lives each day for peace,

May their hearts glimpse providence at the heart of history.

That those who make riches from violence and war,

Might hear in their dreams the cries of the lost.

That we might see through our fear of each other,

A new vision to heal our fatal attraction to aggression.

That those who enjoy the privilege of peace,

Might not forget their tormented brothers and sisters.

That the wolf might lie down with the lamb,

That our swords be beaten into ploughshares.

And no hurt or harm be done,

Anywhere along the holy mountain.

A Letter Writing Ritual

These letters were given to me after my Gran passed 15 years ago, they were found among others that I wrote in a treasured box she kept. She is now a well and wise ancestor who I feel as deeply connected to as when she was alive. And so this winter, I am continuing to write to her sharing about my inner and outer landscapes.

Art by Johannes Rosierse

“You have a touch in letter writing that is beyond me. Something unexpected, like coming round a corner in a rose garden and finding it still daylight.”

Virginia Woolf

Recently, I found a letter posted on 21st June 1999, the summer solstice in the last year of that decade, that I sent to my grandmother, Frances O’Sullivan, my gorgeous “Gran”. I was a teenager at the time away without my family studying Gaeilge/Irish in the Gaeltacht in Co. Donegal. This was my third summer to go away to study Irish and so I was used to the experience by this stage.

As my eyes fall upon my own writing, it’s curious to read now 24 years later what was happening in my inner landscape… how I was feeling, the small little revelations I was having about the language, an experience of a “blind date” that made me laugh so much I was nearly sick, something I have no recollection of now (it must have been a school sketch or show we put on)!

I also shared about my outer landscape, about the Bean an Tí, the “Woman of the House” and her small children who were the age that my own children are now. How they were bilingual and adorable. The Céilí’s, the dances each night and the craic of losing the run of ourselves, swinging one other so hard that we’d take flight during The Siege of Ennis (one of the dances).

These letters were given to me after my Gran passed 15 years ago, they were found among others that I wrote in a treasured box she kept. She is now a well and wise ancestor who I feel as deeply connected to as when she was alive. And so this winter, I am continuing to write to her sharing about my inner and outer landscapes.

Letter Writing Ritual

This is an invitation to write a letter to a well and wise ancestor or a mythic ancestor this Samhain. For example, you might like to write to the Cailleach, the Gaelic Goddess, our Seanmháthair Naofa, our Sacred Grandmother, who is deeply associated with these winter months in Ireland/Éire, the Isle of Man/Ellan Vannin and Scotland/Alba. Or whoever calls to you at this time, listen and you’ll hear them whisper.

The Tradition by Julia Jeffrey

Open up your ritual space before you write, light a candle to honour the flame of your lineage, both clan and mythic ancestors.

Remember, when you handwrite, you are literally shaping your words with your body. Your handwriting is utterly unique to you, and so as you write in ways you create and recreate yourself.

Share with your ancestor about what’s happening in your inner landscape, your world of thoughts, emotions, feelings, sensations and intuitions.

Then share about your outer landscape, what is happening beyond your window in the world? How does the outer world relate back to your inner world?

Write with free abandon in full honesty so as not to lie to yourself or to your ancestor.

What guidance would you welcome in a return letter from your ancestor? This may come to you in the form of a dream, a synchronicity, an intuitive spark - a mirroring back to you.

If ever there’s been a time to remember our global interconnectedness, it is now. Let the Goddess be your guide.

The Otherworld by Tijana

Once you have written your letter, you can place it in an envelope, even address it if you like, allow the spell of your imagination to work its wonder.

Then place your letter on your altar, or a sacred space, or you can write a series of letters and continually wrap them in string. You will know what to do. They are your keepsakes.

In time, reopen your letter and journal in response to the guidance that did come to pass. Perhaps at the Winter Solstice or Imbolc or whatever season you find yourself in.

“She is ideas, feelings, urges, and memory. She has been lost and half-forgotten for a long, long time. She is the source, the light, the night, the dark and daybreak… She is the one we leave home to look for. She is the one we come home to.”

Clarissa Pinkola Estés

Voices of Celtic Wisdom

I am thrilled that I will be joining the teaching team of Voices of Celtic Wisdom. This is a 4-month programme exploring living threads of the earth-based cultures of Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales with song, story, lore and hands-on crafting workshops.

Other teachers include Dolores Whelan, Manda Scott, Angharad Wynne, Tara Brading, Mary McLaughlin, Danu Forest, Dougie MacKay, Seoras Macpherson… and more wondrous souls.

The programme runs from 30th November 2023 to 25th March 2024.

Mythical Disrupter

A culture’s mythology is often located within the traditional. And where you have a racialisation or othering of the mythic or folkloric beliefs of a peoples like in Ireland under colonial rule, the obsession with modernisation can intensify because we have to be seen to be progressing, to be rational, to be intellectual, to lose our “backwardness”. It’s a survival tactic.

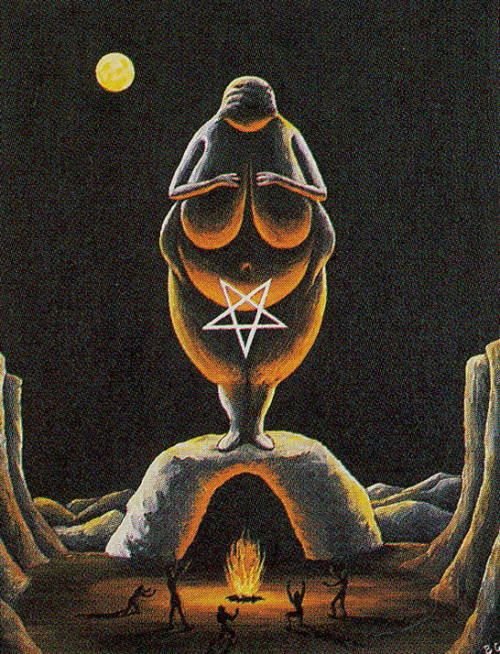

Sheela na Gig by Thomas Sheridan

For 16 years, I worked in global justice and human rights, I’m still involved as a volunteer on the board of an Irish civil society organisation. And so, I’ve spent a lot of time contemplating the idea of human “progress” and “development”. I even ended up doing a masters in the ‘anthropology of development’ to peek beneath the rug or indeed, pull the rug from under myself with all of the lies I had learned from our overculture in the name of progress.

I share this because it’s relevant to how we perceive our ancestors and our mythical heritage.

Of course, development brings its benefits but when understood only as progress in one direction, it becomes a systemic lie, one which we all seem to have to work towards at the expense of our mental health, our bodies, and life around us.

A Comet’s Journey by J.J. Grandville

Development is essentially a Western notion that has no equivalent in many languages. It is not natural or universalistic and does not appear in all cultures. In ways, it is a practice by which the existence and destinies of non-conforming Western societies are formed through Eurocentric ways of imagining and perceiving the world.

This impression of development creates a false polarity between the traditional and the modern whereby the modern is glorified as the universal goal and any deviation is relegated to the primitive, of being stuck in the past.

Sun and Moon by Ernst Steiner

A culture’s mythology is often located within the traditional sphere. And where you have an othering of the mythic or folkloric beliefs of a peoples like in Ireland under colonial rule, the obsession with modernisation can intensify because we have to be seen to be progressing, to be rational, to be intellectual, to lose our “backwardness”. It’s a survival tactic.

A consequence of this is that our mythology loses its power, and we fall out of our enchantment with the world.

Art by Pantovola

So why am I sharing this today?

Well because, I want you to know that mythology can be a form of resistance against the fallacies of our overculture. Indeed, this is one of the roles I believe it is now meant to serve. Mythology isn’t simply a wander through traditional fantasy, nor is it static or meant to remain in the past, it is meant to evolve and it is essential to our times. As Jung once said,

‘Enchantment is the oldest form of medicine’.

Mythology is a gateway to enchantment. It doesn’t need to kill itself worrying about progress because mythology is timeless just like your soul is. And like your soul, it is also called to be in service to the times we are born into.

So as you begin another week, another day, another hour, another minute, remember that your soul is timeless and by being on this path, you are breathing life back into our mythology. You, my love, are a mythical disrupter.

To Hold it All by Sarah Brokke

Sacrifice of the Goddess

Here, we can see an allusion to the death of a Great Mother, the Goddess of Vegetation and the Harvest presented in a way that was necessary for human evolution as the rising masculine consciousness symbolised by Lugh, was now the way forward.

Demeter Mourning for Persephone by Evelyn de Morgan

In Ireland, it is the Goddess Tailtiu, foster-mother of the shining sun God Lugh who is said to have first cleared the plains to prepare the land for tilling. With her supernatural might, Tailtiu felled great forests to make way for our transition to agriculture.

When her feat was complete, she lay down and died of exhaustion.

Lugh, grief-stricken honoured Tailtiu’s dying wish by creating Óenach Tailten. These were Olympic-style games on the land which she had cleared to celebrate her grand endeavours and the harvest season that became known as Lughnasa.

Óenach means 'reunion' or 'popular assembly' symbolising the games, races and tournaments that were part of these Tailteann festivities. Lugh himself led the inaugural contests of horse racing and warrior combat.

The Tailteann games were celebrating during Lughnasa until the 1770s and then experienced a short revival in the 1920s following the War of Independence.

Photo from the Tailteann Games in 1924

An excerpt from the Dinshenchas, the ancient Lore of Places about Tailtiu:

"Her heart burst in her body from the strain beneath her royal vest; not wholesome, truly, is a face like the coal, for the sake of woods or pride of timber.

Long was the sorrow, long the weariness of Tailtiu, in sickness after heavy toil; the men of the island of Ériu [Éire, Ireland] to whom she was in bondage came to receive her last behest.”

The Lady and the Green Man Mask by Robert Gould

Here, we can see an allusion to the death of a Great Mother, the Goddess of Vegetation and the Harvest presented in a way that was necessary for human evolution as the rising masculine consciousness symbolised by Lugh, was now the way forward.

It’s interesting to draw parallels here in the Irish mythical context with the idea that the evolution of agriculture and control of nature's resources led to the emergence of private property and gave rise to the overthrow of any lingering matricentric structures.

A beautiful friend of mine recently brought me back some sheaves of wheat from Teltown in honour of Tailtiu. She collected these early one morning as two hares, symbols of our mythical ancestors, lept through the fields.

While participating in a live storytelling session where we were encouraged to make as we listened, with a sheaf, I wove these rough and wild, ‘Tailtiu Prayer Beads’ using the kernels, some stalk and a peacock feather. In the rhythm of my threads, I felt all that is woven into Tailtiu’s sacrifice.

This is an invitation to weave your own ‘Goddess Beads’ this Lughnasa season to acknowledge the Great Mother and the endless sacrifices she has made on our behalf. And as we can see in her climate revolt, she is not passive but raging in sacrifice. She has had enough. As have many of us.

Women have forever been weavers of human fate and so with each bead you thread for the goddess, be present to the possibility of a new destiny we can weave together, perhaps one on the loom of the Great Mother.

A Dream of Sinéad

Sinéad never went into the shop of my dream in fact, she was always the one pulling us out of it. Some of us would falter like a lost sheep and wander back in, and she’d pull us out again. But she did much more than that, she sought to demolish the shop altogether.

Faith by Jeanie Tomanek

My dreamworld and all that surfaces from its abyssal waters is one, if not the, most crucial guides in my life. Dreams rolled in like a thick foggy presence since early childhood. A density that for a long time seemed more curse than blessing. My dreams are my truthtellers showing me the truth of my life through symbols. Symbols that I then have to spend time deciphering. My dreams force me to do the work.

As many of you will know, the dreamscape is something I incorporate into my work as like the Otherworld, dreams can emerge from the sea of the collective unconscious. I go back to university in Ireland this September to study dream more intensely with Jungian psychology and art therapy. I rarely share a dream before working with it – be that through writing, drawing, art, making, imaginal journeying, moving as the dream, or exploring it through analysis. This takes time and I like to metabolise before sharing if at all. But today, I share a dream with you I had last Friday night.

I share it because it featured Sinéad O’Connor, our beloved Banríon who passed away last week. It is a sorrow-stricken and painful time in Ireland as we honour Sinéad who used her voice and art to fight so courageously to expose the horrors of Irish society. She did so with relentless soul, understanding inherently that without the nigredo, we can have no alchemy, we can’t transform. And Ireland desperately needed and still needs to transform.

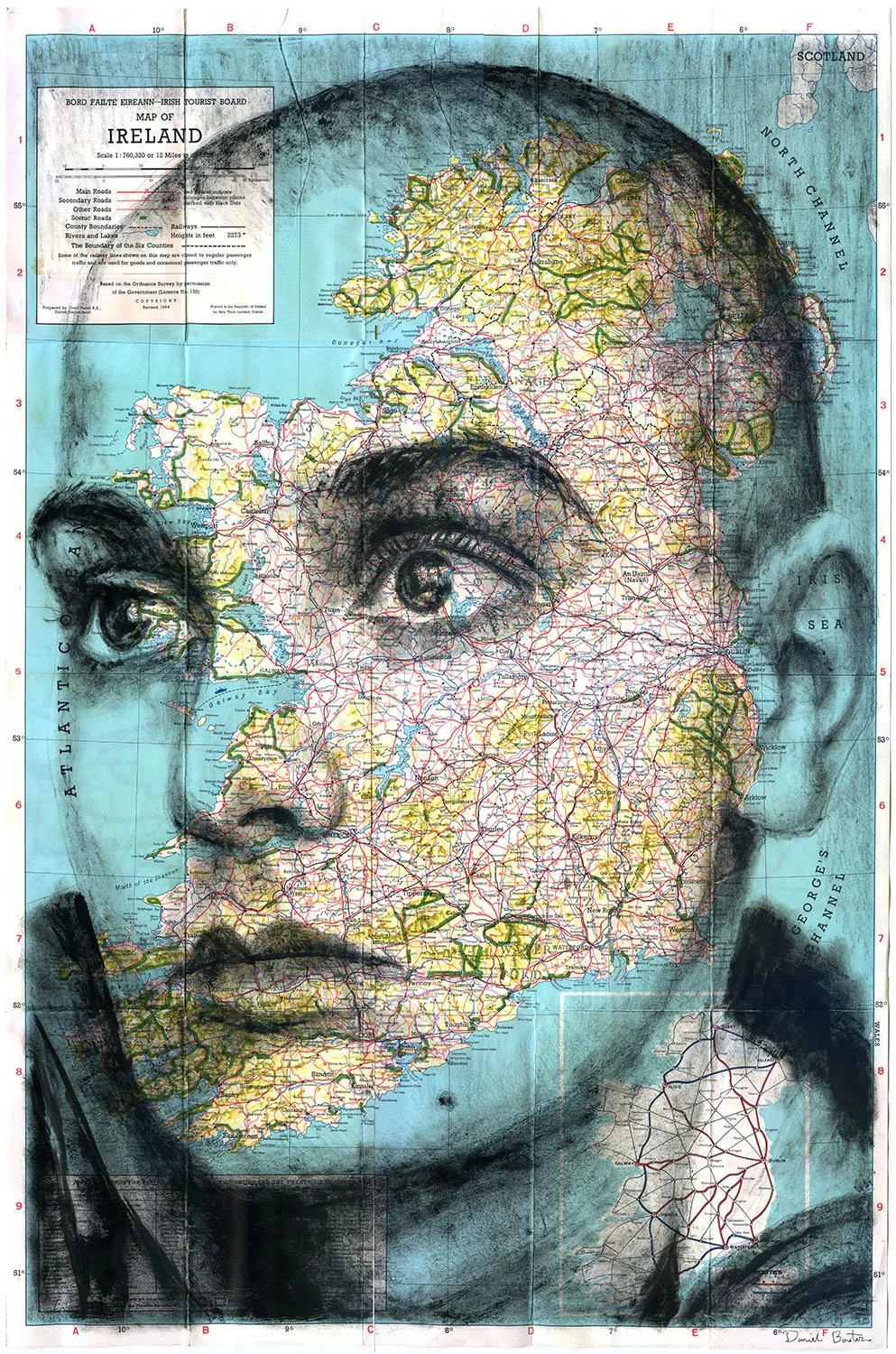

Sinéad O’Connor by Daniel Baxter

So the dream goes…

‘In the dream, I was creating three huge sculptures of Sinéad O’Connor’s head and shoulders. The first sculpture of Sinéad was silver, the second was gold, the third was red-gold. These were positioned high on a hill. When I came back down to the foot of the hill, I saw a huge shopfront there. Its glass was clear and encased in lovely sage green wood. It looked like a bookshop. When I looked through the glass, I saw that the shop was split into two levels. There was a ground floor and an upper floor. The left side of the shop on both levels was filled with hundreds of women who were dressed like Little Bo-Beep from the nursery rhyme. When I looked to the right side of the shop, on both levels I saw hundreds of men wearing suits. The Suits were speaking tyrannously at the Little Bo-Beeps who mumbled passively and laughed nervously in response. I then noticed a big “Closed” sign on the door and the dream voice said to me, “You can never go in there again.” I wake up.’

I will brew in the broth of this dream but there are bubbles boiling to the surface. The creation of the sculptures of Sinéad positioned high on the hill are symbolic of her being a personal icon and particularly during my formative years in the grimness of 1990s Ireland. I went to the same secondary school as Sinéad did for a time years after her, and so, she was in ways, a school symbol for the rebel many of us longed to be and tried to express. Some time ago I was asked to create a vision board of my feminist heroes and I printed, cut out and glued a picture of Sinéad front and centre, which felt symbolic as teenage me despite being awestruck by her had no real notion of the profundity of her courage.

I read in the Irish media recently,

‘Sinéad O'Connor was everything Official Ireland didn't want women to be, and we loved her for it.’

From ‘Troy’ by Sinéad O’Connor

The dream is oversimplified in terms of gender, we know the Little Bo-Beeps and Suits are not simply women and men. Yet, it shows a patriarchal presentation of ‘power over’ and the expectation of women and marginalised communities to be passive recipients of ‘authority’. In her life, Sinéad was consistent in questioning - who is the ‘authority’? Who holds the power? Who says so? How did they come to hold this privilege? Is this power over or power with?

I also feel a charge in that Little Bo-Beep is a maiden. As women, we often get locked in eternal maidenhood, in a prison where we can’t evolve into the Great Mother or crone of our lives. We’re not allowed to age, to evolve in wisdom. The scrutiny of women’s ageing is a form of cultural control and to a terrorising level for any woman in the spotlight like Sinéad. As Naomi Wolf said in the Beauty Myth:

‘The beauty myth is not about women at all. It is about men's institutions and institutional power.’

Sinéad O’Connor was never passive in her maiden expression. In her memoir, Rememberings, she shares the story of her decision to shave off her hair in response to her record label executive who:

‘…announced he’d like me to stop cutting my hair short and start dressing like a girl. He was disapproving of my recent attempt at a (very short) Mohawk. He said himself and Chris would like me to wear short skirts with boots and perhaps some feminine accessories such as earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and other noisy items one couldn’t possibly wear close to a microphone.’

After the deed was done, her head shaved in defiance, she says:

‘Me? I loved it. I looked like an alien. Looked like Star Trek. Didn’t matter what I wore now.’

Edra: Queen of Pentacles as the Great Mother by Barbara Walker

Sinéad never went into the shop of my dream in fact, she was always the one pulling us out of it. Some of us would falter like a lost sheep and wander back in, and she’d pull us out again. But she did much more than that, she sought to demolish the shop altogether.

Let me tell you, I’ve been the Little Bo-Beep many times in my life and I’ve also stood for long periods outside looking in with despair. I will never be as courageous as Sinéad O’Connor and I will be forever grateful to her for the permission she gave Mná na hÉireann to be our bold and brave selves. Because being on the outside can be terrifying.

I’ve often wondered when standing outside, what got me here? And it’s only recently that I’ve realised when all of the veils of illusion I hold finally burn away - if they ever do, it’s that part of me that’s left, the essence of my being, my soul that puts me there and like the dream voice says, “You can never go in there again.” It’s the part of me that lives through the belief that reclaiming and evolving the mythic feminine for our times is a powerful form of resistance and disruption from our patriarchal and capitalist overculture.

Like Sinéad, we have to use our creativity, our art, our diversity, and our voices to stand together in the truth of who we really are and who we are called to be. We have to give ourselves permission to evolve.

Together, we can demolish the shop so that all we see is Sinéad’s silver, gold and red-gold wonder shining down on us and perhaps giving us a wink of approval, or three! ❤️

The Hell Fire Club. Source Viator.

A song that I have been moving, shaking, weeping to, and finding resilience within the past few days is Troy. This is my favourite Sinéad O’Connor song. It’s a masterpiece. And so, I wanted to share the video with you if you haven’t seen it or desire to revisit.

The building that explodes in the video is called the Hell Fire Club on Montpellier Hill, a haunt well known to most Dubliners as it peers in its eery eminence over our city. It was originally an old hunting lodge built by William Connolly in 1725. Following his death it became a club for wealthy Dublin men who dabbled in the dark arts. The devil himself with his cloven hooves is said to have been a frequenter of the Hell Fire Club. In 2016, archaeologists discovered a 5,000-year-old passage tomb on the site. It was long held in folk memory that stones from the ancient cairn was used to build the club itself, which resulted in all kinds of supernatural happenings.

It’s a symbolic video on so many levels. FEEL the feminine, the Great Mother, Sinéad O’Connor, roar.

We all have a Mythical Lineage

We all have a mythical lineage. But what happens when we are severed from our mythical traditions? How do we dream the myth onwards? How do we go walkabout in the cultural dreamtime to regenerate our mythical lineage in service to our lives, our families, our communities, and our world?

Eve (The Dreaming) by Jana Heidersdorf

We all have a mythical lineage. Or many mythical lineages. We all descend from ancestors who were storytellers. Whose mythology told the story of their people—their story, which is now our story to evolve as inherent in these ancestral myths is wisdom we so desperately need for our times. As Jung said, we must:

“…dream the myth onwards and give it a modern dress.”

But what happens when we are severed from our mythical traditions? How do we dream the myth onwards? How do we go walkabout in the cultural dreamtime to regenerate our mythical lineage in service to our lives, our families, our communities, and our world?

Well first, we must understand that this severance is a problem. A problem that together we can seek to solve. As the fairytale always tells us, each one of us holds the golden key.

The Golden Key by John Bauer

Mythological Displacement

Before I founded my business, the Celtic School of Embodiment, I worked for 14 years in global justice and human rights. During this time, I met many people who were experiencing ‘displacement’ either within their own country’s borders as an Internally Displaced Person (IDP) or across an international border, as a refugee. Displacement is the coerced movement of people from their home territories due to life-threatening factors like natural disasters, climate-induced disasters, war, persecution, corruption and human rights violations.

Displacement forces people to flee their homes, often that of their ancestors, and in consequence, causes immense psychological and bodily trauma. In addition to the wounding of the life-threatening event itself, displacement ruptures peoples’ connections to the cultural psyche and their mythological roots; the stories of their people. In the West where we have succumbed to the plague of rationalisation, the loss of our native myths may not seem as grave as the loss of life. It’s not. And yet, it has serious ramifications, which I believe we are only starting to see particularly in countries with a history of settler colonisation.

Myth is not primitive nor is it fabrication nor is it children’s stories. There is no singular purpose to myth, but in most cultures, myth facilitates the conditions for people to engage in the sociocultural, natural, and supernatural worlds that surround them and illustrates through story a range of effects that individual action can have on these multiple worlds. It can contribute to a person’s physical, mental, emotional and spiritual wellbeing. Myth and place are often inextricably linked. Myth helps people anchor in their physical and metaphysical place in the world. Not that this needs to be static. Any romanticised notion of ‘pristine’ mythology that is void of an agenda and has been isolated from interactions with other peoples and cultures, is a fallacy.[1] Myth is fluid and should flow with the times.

Still, we are living in an epoch of mythological displacement. In a time when people are displaced or have been moved away from their mythical lineage. I believe that this is detrimental to our wellbeing and I see from the women I work with, how this is amplified when we are not living on the land of our ancestors. While some of us like myself may live in the places where our forebears were born and died, many more do not. Sometimes that is by choice, and other times it is due to factors outside of our control like ancestral migration, colonisation and displacement. Yet for all of us, the felt sense memory of our ancestral home remains buried in our bodies. Just as the old bone woman haunted Gobnait (you can find this tale here) from beneath the top waters so too does ancestral memory haunt us from the unconscious, begging for our attention.

Amžinybė (Eternity) by M. K. Čiurlionis

A History of Displacement

For a small country, Ireland has a colossal legacy of displacement. Numbers vary but the Irish Diaspora is around 70 million people. Of these, 36 million are in America. The remainder are in the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, and small populations in Continental Europe and Central and South America.[2] A historical catalyst to this was the Irish Famine, An Górta Mór, ‘The Great Hunger’, which was the greatest social disaster in 19th century Europe. Over 2 million people, a quarter of the population either died or emigrated. Ireland was under the rule of the British government at the time whose policies premised on racism, classism, and structural violence did not provide an adequate response, it failed the Irish people.

There were aid efforts within Ireland, Britain, and across the world. One donation that is remembered with reverence within Irish cultural memory is that of the Choctaw Nation who gave $170 to relieve famine suffering. This generosity came from a people who at the time were experiencing ethnic cleansing and forced displacement by the American government led by a Scots-Irish descendant, President Andrew Jackson. To take action to ease the suffering of another peoples amidst the horror of their own suffering was a profound act of human solidarity. In the Choctaw myth of emergence, the people are said to have emerged into this world from a mother mound, Nanih Waiya, ‘Leaning Hill’. In Irish tradition, the Áes Sídhe, the ‘People of the Mound’, our supernatural ancestors and otherworldly beings emerge from the fairy mounds, the hallow hills, and the Otherworld to interact with our world. Like in these instances where land and myth are interwoven, the displacement of peoples from their ancestral homes can be spiritually devastating.

Kindred Spirits sculpture in Midleton, Co. Cork honouring the contribution made by the Choctaw to starving Irish people in 1847

Subtle Displacement

Mythological displacement does not only happen with the forced movement of people, it can occur in more seemingly subtle ways. One example of this is the displacement of a native language with a non-native tongue. We see this with Gaeilge (Irish Gaelic), the Irish language and English. Every placename in Ireland tells a story. When you read Irish mythology, you will find long passages telling the story of how a placename came to be. Yet the history of place is complex in Ireland because our placenames are no longer in our mother-tongue, they were anglicised. This not only displaced the majority of the population from our language but also from our deeper sense of place and ancestry on our land.

To provide an example, a town near where I live is called 'Ardee'. Its meaning is hidden in its anglicised form. The Gaeilge for Ardee is ‘Baile Átha Fhirdhia’ which translates as 'The Townland of the Ford of Ferdia'. The story of this place is about a devastating duel at a ford between two warriors, Cú Chulainn (Koo Chul-an) and Ferdia (Fer-dee-ah), both of whom trained under the talented warrior woman, Scáthach (Scah-hock) on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. Not only were Cú Chulainn and Ferdia brothers in arms but some believe, potentially lovers. You can know none of this when you know the town only as 'Ardee'. Like how modern branding works, this is an incredibly effective tactic of assimilation.

Scáthach by PJ Lynch

Capitalist Displacement

Culture is a natural phenomenon across all human societies but culture itself is not natural, it is learned. Culture's mode of communication is predominantly symbolic. Different cultures share information in different ways, but they do so through symbols. These symbols could be the likes of words, gestures, behaviours, actions, and objects that are all inferred with meaning by a given culture. From birth, as you grow, you absorb these symbols and learn how to speak your culture fluently. Capitalism also behaves like a culture. It is not natural, it is constructed. Capitalism diffuses its own series of cultural symbols through the image of global brands (think Apple) that mass media then manipulates us into consuming through influencers. In capitalist spirituality, deities are celebrities, sites of worship are stores or anywhere we can consume, and our votive offering is money.

With capitalism, comes the idea of ‘development’, the lie of eternal progress that we all seem to be working towards. Some countries are ‘developed’ so better, others are not so worse. Development is a Western notion that has no equivalent in many languages. It is not natural or universalistic and does not appear in all cultures. Rather, it is a practice by which the existence and destinies of non-Western societies are formed via a Eurocentric mode of imagining and perceiving the world.[3] This impression of development creates a false polarity between the traditional and the modern, a deception whereby indigenous peoples are often characterised as primitive, having existed without history until the arrival of Europeans.[4]

The idea of modernisation has been propagated with such force globally that it is glorified as a universal goal and any deviation is subsumed under a negative, ‘traditional’ classification. Mythology exists within the traditional. It is not modern and so is perceived as less than. Where you have a racialisation or othering of the mythic or folkloric beliefs of a peoples like in Ireland under British rule, the obsession with modernisation intensifies because we have to be seen to be progressing, to be rational, to be intellectual, to lose our backwardness. It’s a survival tactic. A consequence of this is that our mythology loses its power, and we fall out of our enchantment with the world. Writing over one hundred years ago, German Sociologist Max Weber warned:

“As intellectualism suppresses belief in magic, the world’s processes become disenchanted, lose their magical significance, and henceforth simply ‘are’ and ‘happen’ but no longer signify anything.”

Dancing Fairies by August Malmström

White Supremacy Displacement

Capitalism’s greatest lover is white supremacy culture, an ideology that creates a hierarchy of imagined racialised value, where like modernisation, whiteness or white culture is the desired result; white middle and owning class to be specific. It constructs who is of value and human, and who is not in the name of profit, power and ‘progress’ at all costs.[5] This is a sinister form of colonisation, of ‘power over’ as it displaces us from ourselves, our hearts, our bodies, our spirits, one another, and nature.

In White Supremacy Culture – Still Here, Tema Okun and colleagues at dRworks articulate how white supremacy culture violates the humanity, ways of knowing, ancestral land and livelihoods of indigenous people, while exoticising, romanticising and culturally appropriating the wisdom and customs held within these communities. Indigenous people often maintain historical continuity with pre-colonial culture and form non-dominant groups within society.[6] We see this in Ireland with the Traveller (Mincéirí) community who have been vilified, ostracised and forced to ‘settle’, a form of displacement, by the Irish government, as Ireland upon independence used much of the same institutional structures imposed by the British Empire.

Even in our education system, which mirrors the British system and was formed in collusion with yet another colonial power, the Catholic Church, our mythology is taught as imaginary tales for children. Okun stresses how academia defines the “classics” as Greek and Roman, white and male. ‘Classic’ conjures the image of the highest possible quality—forever—and in this way gives superiority to a particular way of knowing so that Greek and Roman becomes the mythology of the West. These mythologies do, of course, speak to archetypal patterns that appear cross-culturally and are fundamental to understanding the Western Psyche as are their many Egyptian roots. But we have access to a rich broth of other mystery traditions, some of which have been relegated to the margins for not conforming to this model of classic. Why not have this, and more please?

“Looking back behind the modern severance of spirit from nature, we can find an important source of Western culture in the myths, art, music, folklore and traditions of pre-Christian Ireland. This material is as important for understanding ourselves as Egyptian, Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian influences.”

Sylvia Brinton Perera, The Irish Bull God

Irish mythology does not equate to whiteness. Irish bodies come in a gorgeous spectrum of colours and diverse lineages. This extends beyond our small island to our Diaspora, where for example, it is estimated that 38% of African Americans have Irish Ancestry.[7] This fills me with hope for our mythology as our diversity can fuel innovation and creativity. My work is my way of weaving a new tapestry for our mythical lineage but we need many diverse threads!

Women in Biskra Weaving the Burnoose by Frederick Arthur Bridgman

The Legacy of Mythological Displacement

I work predominantly with women who are first-generation Irish, or of Irish or wider ‘Celtic’ heritage. 80% of the women who cross my threshold live beyond Irish shores. I see this legacy of mythological displacement everywhere in my work. Common themes that emerge from my clients and community are:

Feeling disconnected from their lineage(s)

Feeling like they don’t know where they belong

Identifying as biracial or multiracial and navigating multiple lineages

Holding shame about not knowing more about their mythological heritage

Carrying intergenerational grief and trauma

Being haunted by the ghost of ancestral loss that they cannot make sense of

Seeking and, or, potentially appropriating from other cultures, or fear of doing so

Being a settler on the stolen land of indigenous peoples

A Remedy for Mythological Displacement

So, what’s the remedy? How do we travel the road from mythological displacement to finding our way home? I don’t live in your body so it would be remiss for me to dictate a solution to the complexities of mythological displacement. That acknowledged, in my experience, there are three standing stones that generate the soulful conditions for you to (re)discover your own location for home within your lineage.

The Wild Swans by Jackie Morris

1. Become Intimate with Your Mythical Family

You are not simply your life and your life simply you, there are spiritual forces that arise from the collective unconscious—your mythical kinsfolk—who are naturally invested in your life. Who conspire to guide you to self-actualisation, to fulfil your life’s Calling. This cannot happen without reciprocity—you have to be interested in them to see their interest in you.

Tend to the archetypes that your ancestors brought to life to shape their world and the native faces they bequeathed these archetypes—the goddesses, gods, and mythical beings of Irish mythology. This is your mythical family. If you hold multiple lineages, invite your full family in, all lines. Jung believed that ancestral experience remained alive within the sea of the collective unconscious. Myth is one of the most powerful ways we can access this unconscious so that we can learn from our mythical and human ancestors. What would they wish for us to know?

In this way, myth is always evolving and can serve to illuminate the foresight we need for our lives, our families, our communities, and our world. We are living in an unprecedented era of crisis as our planet revolts through climate change against the toxicity of our relationship with it, which I believe mythological displacement exacerbates. Deepening your relationship with your mythical family is deepening your relationship to Mother Earth. We have to dream with our mythical ancestors and allow these visions to be of service.

2. Unveil your Divine Feminine Heritage

When we venture into the Otherworld of our mythical lineages, we see how the ‘original’ sources are often tainted with a patriarchal hand as is the case with Irish mythology and its Christian scribes. We have to lift the veil in search of the feminine, to excavate her from the ashes of mythological memory. It is no coincidence that the domination and subjugation of nature and the feminine are killing our planet. And so, when we find the feminine in our myths, we must allow her wisdom to metabolise through our bodies so we can inhabit her more fully. We must welcome the full spectrum of the feminine into our lives so that we ourselves can become more alive. She has been missing and we are dying without her. Rest assured there is no shortage of big feminine energies in Irish mythology. We have much to work with.

3. Partner with Your Body

You could go and read books on Irish or Celtic mythology and the feminine, which are still few and far between, we desperately need many more. Yet for me, what is missing entirely from experiences of myth and the feminine in the Irish and Celtic context, is the body. To paraphrase Marion Woodman, we can only hear our authentic voice when we discover and love the goddess lost within our rejected body. And so let me repeat what I said above, it is no coincidence that the domination and subjugation of nature and the feminine—and the body—are killing our planet. We have rejected all three. We have displaced all three. When you drop the stories of your mythical ancestors into your body and allow them to coarse through the veins of your own life stories, this is where the magic, the re-enchantment happens.

Samhain by Wendy Andrews

I Feel Like I’ve Come Home

What happens when you become your own custodian of these three standing stones? It may sound like a cliche but the most common response I hear is, “I feel like I’ve finally come home.” This is frequently accompanied by:

Deeper acceptance and love of self

Honouring your Irish or wider Celtic lineage, and other lineages from an embodied and internally resourced place

Rootedness in your own sense of what it means to belong in this world

Release from ancestral grief and trauma

Confidence to engage in cross-cultural relationships in celebration of our human diversity and our interconnectedness

Trust to reimagine your lineage(s) free from dogma and make your own poiesis with this in service to others and these times

And when you stir feminine stock into this broth, women are energised with personal:

Sovereignty: A stepping forth into life as an embodied expression of power within, as a sovereign woman

Sensual Aliveness: A cultivation of your external senses, along with the nebulous world of your internal felt senses as a gateway to living a full-flavoured enchanted life

Becoming: An implosion of creative lifeforce. Surrendering to cyclic rhythms and embracing all seasons in acceptance of your ever-unfolding unto life

‘“O Brigit!” said Ogma, “before you go tie a knot of remembrance in the fringe of your mantle so that you may always remember this place—and tell us, too, by what name we shall call this place?” “Ye shall call it the White Island,” said Brigit, “and its other name shall be the Island of Destiny, and its other name shall be Ireland.” Then Ogma tied a knot of remembrance in the fringe of Brigit’s Mantle.’

- Ella Young, Celtic Wonder Tales

You remember the knot in your mantle, I know you do.

References

[1] Wolf, E.R. (1982) Europe and the People Without History. University of California Press

[2] Irish Emigration Patterns and Citizens Abroad 2017, Department of Foreign Affairs, Ireland

[3] Tucker, V. (1992). The Myth of Development: A Critique of a Eurocentric Discourse. In Munck, R. & Hearn, D. (eds). Critical Development Theory: Contributions to a New Paradigm. London: Zed Books

[4] Sahlins, M. (1999). What is Anthropological Enlightenment? Some Lessons of the Twentieth Century. In Sahlins, M. (eds.) Culture and Practice: Selected Essays. Zone Books: New York

[5] Okun, T. (2021) White Supremacy Culture – Still Here. whitesupremacyculture.info

[6] United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

[7] African American Irish Diaspora Network

Goddess Gobnait & Her Nine White Deer

Gobnait (Gub-nitch), once a living Saint and a pre-Christian goddess. A Sister-Saint of Brigid, the holy woman and goddess of poetry, healing and smithcraft. Both are venerated at Imbolc, the awakening time, both women lived in the 5th and 6th centuries. This is my retelling of Gobnait’s story.

Beehaloed by Lea Bradovich

Gobnait (Gub-nitch), once a living Saint and a pre-Christian goddess. A Sister-Saint of Brigid, the holy woman and goddess of poetry, healing and smithcraft. Both are venerated at Imbolc, the awakening time, both women lived in the 5th and 6th centuries. This was an era of monumental change in Ireland. Christianity had arrived on our shores threatening what we now call ‘Pagan’ spirituality, the native cult, the Old Ways. In these early days, there was a fluidity between the old and new cults as both Gobnait and Brigid in Goddess and human form attest to. Yet, over time with Christianity, patriarchy, the rule of the father, had the opportunity to deepen its presence and seep into every cultural crevice in Ireland, separating us from the Spiral, the original image of the Great Mother.

This is my retelling of Gobnait’s experience.

Gold plaque embossed with winged Bee Goddess from Camiros, Rhodes, 7th century BCE

Gobnait Speaks:

A child of The Piracy born from the loins of a sea-raiding father, I was without a mother lost in the swell of a man’s world. I was loved in ways, in the way one loves a possession. Something you own, perhaps even something you treasure. Until its shine dulls, and your fondness dulls with it.

As Woman, I never belonged to my father’s crew. I grafted like the men around me until my skeleton shook. To my shame, I raided with them. I plundered, I burned villages to ash, numbing my shrieking heart in trade for recognition. But the recognition never came. At least not in the ways it did for my pirate brothers.

I longed for a mother. For my physical mother who hung like a rhythmic ghost over the waves. For Máthair, ‘Mother of All’, who was just as ghostly. An apparition, a rubbing of fingers and thumb, I’d try to grasp her with my full hands for they told me she used to be everywhere. Once worshipped as the Spiral. In every tuath, every tribe. Máthair and her tomb womb of birth, life, death, and rebirth.

If she was so venerated. Where was she now? Why had she abandoned me? I resigned myself that she was but an old bone woman who haunted me from beneath the top waters. A make-believe story I wished had never fallen into my ears. For hope was like sepsis infecting my numbness. I could not risk the thaw.

Each new moon cycled into form, and I bled alone, away from the crew. With my blood, came imbas forosnai, the prophecy, the sight that illuminates. In my maiden bleeds, I would return on the waxing days and share my visions. Warning of a failed raid, of looming misfortune, of losing our own good men.

The imbas rattled some of The Piracy, not least those who remembered the Old Ways. But my father dismissed it as women’s nonsense, of the natural hysterics that I was born to express, and my mother before me, her mother before her. Raids failed, misfortune came, men died. And yet my voice never grew in power. Only their glares of disdain.

Then the white deer came.

In the chaos of a mainland raid, I fled The Piracy, sprinting until my legs were taken from under me, I tumbled into the druid of the forest, an old oak. My face dizzy in its roots, I looked up and saw the white deer, a fleeting shadow. I had no way of apprehending the later significance of this otherworldly beast. How could I, for I was still a child of The Piracy.

I dragged myself upright back into my feet and began the voyage west to Inis Oírr, the eastern island. My father would not seek me there for there was no raiding to be had. As I rowed into its limestone shores, I wondered if he cared that I had disappeared. Did it matter?

Early on Inis Oírr, I found myself ill with a guilt-ridden yearning for The Piracy. Captive to the grief for that which is known. As I grieved, a ripping wind keened in my ears and tore shreds of flesh off my bones, pulling skin away piece by piece into the bitter air. There was a pleasure in this pain. I felt a slow unearthing like the island was trying to pare me back to who I was before. To the someone I was in a time before I knew myself.

Flesh fell and fresh germination saw me curate a sanctuary on the island. Not many came but those who did flickered with light. On this wild isle, they had a soft lumination to them. A tender hand on the shoulder, a sharing of lore, a wink of the eye. I was not used to land-living folk or indeed to women at all. I started to feel a connection weave, a white thread forming.

At night, I dreamed of someone calling my name, Gobnait. The sea whispered through the wattle walls:

“Gobnait, Gobnait, Gobnait, A Stór,

Queen of Honey, Lady of Smithcraft,

Nine White Deer, Ninefold Priestesses,

A Daughter of the Spiral.”

It got louder and louder until the dream flowed out of the Otherworld into this physical realm. I dreamed while awake. A woman stood before me. They would later say it was an angel that appeared to me. And she was. An otherworldly woman from Tír na Ban, the Land of Women. Cloaked in a white mantle, her hair spilt down her breast in a raven glow. Eyes of pale amber, she had a foxglove blush on each snowy cheek. Her lips were Parthian red as she gently spoke my name, “Gobnait.”

Then offered me a silver branch of apple blossom, which bore apples while in bloom. I took a silver apple and broke its skin with my teeth. To my wonder, it wasn’t juice that flowed but a sweet honey elixir. The angel told me that despite my finding a sanctuary on Inis Oírr, this was not my home. I was to travel back to the mainland and whence I fell upon the plain where nine white deer grazed, this would be my place of resurrection.

I had no idea what she meant by “my place of resurrection”, but I knew in the pulse of a vein, I had to answer her Call. And so, I travelled. I saw three white deer, six white deer, but never nine. I spent time in many tuaths, in holy places, still as soon as I felt settled, the nine deer would whisper once more and I would be gone. I trusted, I had no choice, I was ravenous for home.

Black Madonna from The Secret Life of Bees by G. Stoughton

The nine whispers became nine wisps of silver mist that I chased across the land until I climbed down the hill into Baile Bhuirne, the ‘Town of the Beloved’. It was here I saw them. Nine white deer, each with a silver spiral on its hind. As I drew closer their necks guided their noble faces to meet my gaze.

“Máthair”, I gasped.

“Máthair”, I cried.

“Máthair”, I wept falling to my knees.

I could feel the spiral activate within me, spinning in my mind, my heart, my womb. A triple spiral. Spinning as Máthair, as birth, life, death; rebirth, life, death. I was reborn. There was no logic here, only a love-induced surrender and my knowing that I was a Daughter of the Spiral. I had always been a Daughter of the Spiral. I just had to find my way home.

As Máthair moved within me, the silver spirals on the deer hinds began to swirl. And before my soaking eyes, each of the nine deer shapeshifted into a woman wearing a white mantle. I recognised one of these women as the angel. They walked towards me, across the footplains of The Beloved and wrapped a violet cloak around my shaking frame. Surrounded by my Sisters I heard myself sob, “This is my place of resurrection.”

Me squinting with all the light around St Gobnait’s shrine in beautiful Ballyvourney

And it was, for I was home both within and without. I apprenticed myself to these women who would become my ninefold priestesses. I (re)learned the Old Ways of Máthair, of working with the Spiral to serve my tuath and my times. I rooted in the lineage that had always been waiting for me. Our community burst into the land and the people flourished. They called me Queen of Honey and Lady of Smithcraft. I with my healing bees and my moulding the nectar of earth, her ore for smithing.

As one of the elders, a file poet-seer once told me, “When you die Gobnait your soul will travel through time in the form of a bee.” If you are reading these words, perhaps it has come to pass.

I found my place of resurrection.

Will you find yours?

Mythical Arts Practice: The Morrígan’s Tresses

This image of the Morrígan’s nine loose tresses became a source of fios for me. Thrice the sacred triple, nine is a mystical number in Celtic mythology. The nine tresses of the Morrígan unbraid themselves and flow outwards to other sacred nines…

The Mythical Arts

Today, I share a nourishing, enlivening and powerful mythical arts practice with you.

So what do I mean by the ‘mythical arts’?

Well firstly, art can be an embodiment process, an experience of the body. Art is often infused by fios, the Irish word for otherworldly knowledge or wisdom gained through divine inspiration in relationship with the Otherworld, or imbas the light of foresight - but it is brought into form through the body.

Secondly, the mythical arts is any way that we breathe life into our mythology through our creative expression. This could be storytelling, poetry, written word, drawing, painting, crafting, sculpting, song, music, movement, dance, theatre, photography, film-making, herbalism, gardening… I could go on and on.

In fact, for the mythical arts practice I’ll be sharing with you today, I don’t know what category it falls into. Crafting perhaps… it doesn’t matter. The mythical arts is about allowing your fios to flow through you into form. Whatever form looks like to you.

You do not need to be an ‘artist’, you simply need to be your own Bean Feasa, the wise woman or Duine Feasa the wise person who embraces their fios and allows it to flow.

Tresses of the Morrígan

I call this practice ‘The Morrígan’s Tresses’, which came from my leadership programme, the Sovereignty Goddess Incubator. The Morrígan or Morrigan is an embodiment of the dark feminine in the Irish mythical tradition. Creation and death, life-giving, life-taking, are dual aspects of the Great Mother of birth, life, death, and rebirth. As a descendant of this Great Mother energy, the Morrígan is an expression of the darker, necessary aspects of the human experience.

Like the Hindu Goddess Kali, she is a destroyer often destroying what needs to die within ourselves so that we can become more alive. And like the Sumerian Goddess Inanna, she bestows kingship through her strategy, sexual potency, magical shapeshifting and seership as a goddess of sovereignty and war.

In one of her core myths, Cath Maige Tuired, we encounter the Morrígan at a ford in the River Unshin in Co. Sligo. It is Samhain when the veil between worlds is thinnest. The Great Goddess straddles this liminal time with one foot on the river bank to the south, one foot on the bank to the north, her vulva present over the water’s roaring flow. Nine loose tresses fall from her head. It is here that herself and the Dagda, the great god of the Tuatha Dé Danann lie together. So that this place becomes known as the ‘Bed of the Couple', and later, as the ‘Ford of Destruction’ - again fertility and destruction, life and death at play together.

The Number Nine

This image of the Morrígan’s nine loose tresses became a source of fios for me. Thrice the sacred triple, nine is a mystical number in Celtic mythology. The nine tresses of the Morrígan unbraid themselves and flow outwards to other sacred nines:

🌀Nine waves that the Tuatha Dé Danann cast into a storm to stop the Milesians, our human ancestors, from first landing upon Irish shores

🌀Nine hazel trees that drop their hazelnuts into the Well of Segais where salmon swallow them whole and wisdom bubbles. This wisdom is liberated into the land by the Goddess Bóinn, who becomes the River Boyne and similarly, the story of Connla's Well liberated by the Goddess Sinend, the River Shannon

🌀Nine white deer, the symbol of Gobnait, obscure sister saint of Brigid, and her place of resurrection, where she becomes a woman unto herself

🌀Nine generations of birthing pangs that horse goddess Macha with her dying breath spell-casts upon the men of Ulster

🌀Nine Morgens of the Isle of Avalon who were skilled priestesses in astronomy, astrology, mathematics, healing, music, herbal lore, and shapeshifting

I have no doubt there are many more.

Your Nine Braids

And so, you will create your nine tresses of the Morrígan in honour of the Goddess and all of these sacred symbols of nine. You will braid them together with incantation as healing threads. Some say the Morrígan is the mother of Goddess Brigid, and like you would weave a Brigid's cross for protection, here will weave:

Three braids of Gratitude for this journey of life, of your own becoming

Three braids of Desire for your life

Three braids of Reciprocity for the gifts will you bring in service to our world

Femme Se Paignant (Woman Combing Her Hair) by Edgar Degas, 1887-1890

What You Will Need

A stick. I sourced mine from Dún na Rí, King's Court, a beautiful ancient forest in Co. Cavan. I set out with the intention to ask the land for the gift of a stick for this project. I found a lovely mossy one, which I then washed and varnished. You could paint the stick if you desire using acrylic paint so it will last. Or you could purchase a wooden dowel. For me, I love the perfection in the stick's natural winding texture

Three balls of wool or yarn

A strong twine for hanging. I used threaded wire from the local florist

Sacred Steps

Once you have your bits and pieces:

1. Take your ball of wool and cut 27 threads of wool measuring about 60cm in length

2. Repeat for your second ball of wool, then for your third ball of wool

3. Once you have your threads ready, take time to prepare the energy of your space. I got on all fours so my head, heart and womb were level. I began breathing and moving myself into this sacred space. I smudged the threads with the dreaming herb of mugwort

4. Divine each of your bundles of 27 threads into 3 x smaller bundles of nine threads. So if you can imagine, you’ll have three bundles of nine threads for your first ball of wool, three for your second ball of wool, three for your third ball of wool - 9 bundles of 9 threads ready for braiding (stay with me 😍)

5. Then once you are ready, fold your threads in half and loop each of your bundles of nine threads onto your stick. I tied my stick down to keep it still while doing this

6. For each tress, you'll now have 18 threads as they've doubled over

7. What I did then is divide my 18 threads into three bundles of six which I braided together

8. As you go, do not concern yourself with perfection. The Morrígan's tresses are not perfect. This is an embodied experience of creative magic not an exercise to get something 'right'

The Magic Begins

Now the magic begins!

Work intuitively, no need to have everything written out beforehand. Feel into your body and ask yourself:

What are my three Gratitudes?

For each gratitude, thread a braid and invoke out loud your gratitude as you braid. For example, I chanted:

“Máthair, táim buíoch as...”

“Great Mother, I am grateful for...”

If you can, close your eyes as you braid and feel the wool weave through your hands and the sound of your invocation bind the tresses together.

I found myself crying doing this and so I wove my tears into my braids. It felt profoundly moving. Go as you are.

Then once complete, ask:

What are my three Desires?

Continue braiding.

And finally,

What three gifts will I share in service to this world?

We all have gifts to bring. A core tenet of Irish mythology is reciprocity with the Otherworld and so in a way, we have due diligence to share our gifts with the world.

Complete your nine Morrígan tresses. Offer a bow, a nod, a hand on heart, a gesture to the Great Goddess and these sacred symbols of nine. Sit with your braids for a time. It's a moving experience.

And when the time feels right, add your twine or wire and hang your Morrígan's Tresses somewhere you can meet with them regularly. Take your braids in your hand as you walk by, stroke them, tend to them, feel their magic – your magic.

“I know this path by magic not by sight”

I write this from the space between. For a time I have been in the unknown. I feel like I don’t know who I am losing—what parts of me are crumbling—nor do I know who I am yet becoming.

I write this from the space between. For a time I have been in the unknown. I feel like I don’t know who I am losing—what parts of me are crumbling—nor do I know who I am yet becoming.

A silver mist descended and lulled me into a slumber and when I awoke I was in the labyrinth. In a gnarling dark forest with its illusory shadows. I have yet to reach the centre, which in itself is only half the journey, if or rather when I’m to re-emerge.

Being in the void of the unknown feels nebulous, clumsy almost to express because we tend not to spend very long here, frantically scrambling to find our way out—any way out. Or we create another world on top of the labyrinth and climb up onto this. Smoothing its maze over with concrete, dusting off our hands, good luck! but missing our opportunity to uncover new depths within ourselves. I’ve done this time again.

I can’t say I’m happy here surrendering. I can feel an irritated body within a body clawing to get out. To escape from myself. But today I am brought solace reminded of our ancestors and their belief that all life begins in the dark. Our Universe began in the cosmic dark. We dream in the darkness of lidded eyes. It is in this place that all magic originates. Because it is a place of infinite possibilities.

Our forebearers, the filí, the poet-seers and the draoithe, the druid magic-makers understood the prospects of the darkness. You see in our myths and native tracts, poets and druids described as ‘dall’. Dall means 'dark', 'obscure', or 'blind' in Old Irish. You also see the use of the words 'caech', which means 'blind in one eye', 'hidden', 'veiled', 'mysterious', and its variation, 'goll'.

This speaks to their trust that we must enter full or at least partial darkness to access magic. To receive imbas forosnai—the wisdom or knowledge that illuminates, the second sight. However long it takes to come.

Art: La llamada (The Call) by Remedios Varo, 1961

The unknown gifts us with a separate sight beyond ordinary logic, and so we can only “know this path by magic”, not by regular sight. These words are taken from Irish poet, Paula Meehan’s mystical poem, Well:

Well

I know this path by magic not by sight.

Behind me on the hillside the cottage light

is like a star that’s gone astray. The moon

is waning fast, each blade of grass a rune

inscribed by hoarfrost. This path’s well worn.

I lug a bucket by bramble and blossoming blackthorn.

I know this path by magic not by sight.

Next morning when I come home quite unkempt

I cannot tell what happened at the well.

You spurn my explanation of a sex spell

cast by the spirit who guards the source

that boils deep in the belly of the earth,

even when I show you what lies strewn

in my bucket — a golden waning moon,

seven silver stars, our own porch light,

your face at the window staring into the dark.

Art: Moon Falls a Thousand Times by Naeemeh Naeemaei

In my own bucket, I can dream of a golden waning moon and seven silver stars.

Do I know what they mean? No. Not yet.

But that’s the beauty of mystery. The beauty of the dark.

So if you are in, or when you find yourself in the space between, listen for your soul’s whisper:

“I know this path by magic not by sight.”

Mythical Leadership Podcast

I was recently invited back on one of my favourite podcasts, the School of Embodied Arts Podcast with Jenna Ward. Jenna and her phenomenal body of work have been a huge expander for me in recent years.

Our conversation was rooted in this question:

For leaders shifting away from the cultural norms of leadership obsession with “more” “bigger” and “eternal summer/growth”, who can we look to for guidance?

In response, we explored:

🌀How I came to (re)vision leadership through my background as a Feminine Embodiment Coach, Mythologist and Anthropologist

🌀We unpack the current masculine overculture and why it keeps many leaders in their maiden energy

🌀I share Celtic myths, stories and wisdom to reimagine what leadership could look like for modern coaches, creatives and leaders

🌀We touch on the different archetypes we might be playing out as a leader (often unconsciously)

🌀Women, wealth, witches and modern stewardship of money

It’s a rich convo!

Awakening to Brigid’s Time

We are moving away from the dreaming time of the Winter Solstice and awakening with the land as life unfurls to a lengthening of days and the promise of the lighter half of the year to come at Bealtaine. And so, Imbolc encourages you to ignite these questions in your body…

Another threshold time is upon us as next week we will enter Imbolc, the season of awakening in the northern hemisphere.

Imbolc (“Imbulk”) or Imbolg in Old Irish means ‘in the belly’ (bolg is 'belly' in Gaeilge, the Irish language) and is thought to refer to the pregnancy of ewes during this time, marking the beginning of lambing season. Another interpretation is that Imbolc derives from Imfholc, which means 'in the cleanse' (folc is 'wash' or 'cleanse' in Gaeilge).

We are moving away from the dreaming time of the Winter Solstice and awakening with the land as life unfurls to a lengthening of days and the promise of the lighter half of the year to come at Bealtaine. And so, Imbolc encourages you to ignite these questions in your body:

What possibilities are emerging for me?

How might I fuel my creative fire?

Like all of the cross-quarter or earth days in the Celtic Calendar (Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine, and Lughnasa), Imbolc is a fire festival. Most notably associated with Brigid (also Brighid, Brigit, Bridget, Bríg, Bríd, Breda, Bridie, Bride) and her perpetual flame.

Imbolc is Brigid’s time.

In Irish mythology, Brigid or Bríg (“Breej”) is a Goddess of the Tuatha Dé Danann. She is the first woman to keen in Ireland over the death of her son Rúadán. Keening is a traditional form of lamenting, of wailing over the dead as a rite of passage. It is a truly embodied expression of grief. The ancient text poignantly tells us:

"She screamed loudly and finally wept. This was the first time that weeping and loud screaming were heard in Ireland. And she was thus the Bríg that had devised a whistling to signal by night."

And so here we get a felt sense, we can almost hear the original sound of our sacred keen passed down intergenerationally on this island - “a whistling to signal by night.”

Brigid is also referenced in a 9th century text called Sanas Cormaic (Cormac's Glossary) as a triple Goddess—Brigit of the Filí (the poet-seers), Brigit of Leechcraft (the art of healing), and Brigit of Smithcraft:

"Brigit—a poetess, daughter of the Dagda. This is Brigit the female sage, or woman of wisdom, Brigit the goddess whom the filí used to worship for very great and very splendid was her application to art. Therefore they used to call her goddess of poets whose sisters were Brigit, the female physician (woman of leechcraft), Brigit woman of smithcraft, from whose names almost all of the Irish used to call, Brigit a goddess. Brigit, then, 'a fiery arrow'."

This tells us her status was profoundly powerful as the filí ("fil-ee") were members of the Aes Dána ("Aysh Dawna"), the 'People of the Arts', the most highly revered group in early Irish society, and she their patron.

To have a feminine deity of smithcraft is not common. This is at a time when metals were considered to be the embryos of Mother Earth. So, to transform ore into objects was magic manifest.

To this day, Brigid is associated with healing and as a sacred midwife. You'll see Brigid's crosses in maternity hospitals in Ireland.

Birthing Bridget by Dee Mulrooney

Then of course, we have Brigid, the Saint. Today, there are many interpretations of this dynamic woman. Traditionally, it was believed that the Church Christianised the ancient Goddess as a modus operandi of conversion. The Saint herself is said to have been born in 451 CE just at the time of the coming of Christianity to Ireland. Some believe that this saintly Brigid was the Goddess incarnate.

"Brigid, who is for the Irish the most excellent saint, just as the pagan Brigit was the most excellent goddess."

Marie-Louise Sjoestedt, Celtic Gods and Heroes, 1940

Brigid by Courtney Davis projected on to the General Post Office, GPO, in Dublin city centre as part of the Herstory campaign.

For the first time in Ireland this year, we will celebrate our awakening to Imbolc with a public holiday on 1st February in honour of our Brigid (this will officially fall on Bank Holiday Monday, 6th). This feels like an immense moment of reclamation and recognition for the feminine on this land. The flame of the Goddess burns bright in our hearts. ❤️🔥

If you are on Irish soil, there are many events scheduled to honour Brigid, you can discover more here. For all, this is a short blog I wrote last year on Making Crosses on Brigid’s Eve.

It is said that Brigid was born on a threshold, her mother had one foot in the homestead, one foot on the land, and so I’m wishing you the brightest of blessings as you take Brigid’s hand and cross this threshold into the awakening time.

Solstice Blessings from the Breast of the Goddess

At Newgrange, the masculine sun enters the vulva of the goddess penetrating the birth canal with light until it reaches her womb. There, the dreaming remains of our ancestors would have been regenerated with the life of the sun. The goddess’s tomb womb an intermediary between life and death.

Art: The Birth of the Milky Way by Peter Paul Rubens, c.1637

Solstice Blessings!

The winter solstice is almost upon us in the northern hemisphere. The Gaeilge for the winter solstice is grianstad an gheimhridh, which translates as ‘winter sun stop’. This reflects the potency of this time to take a personal, collective and cosmic solar pause no matter where in the world you are; north or south.

We’ve reached the pinnacle of Samhain, the darkest night of the year is coming. We’ve ruptured as death has enveloped the land and for some of us, our internal landscapes.

As we transition now into the dreamtime, the winter solstice appeals to us to ask:

What holy longing calls to me?

What is dreaming through me?

Dreaming in the Tomb Womb

The site most associated with this time of year in Ireland is Newgrange in Brú na Bóinne, Co. Meath. Built c.5,000 years ago, this passage grave and ritual complex is hundreds of years older than the pyramids at Giza and Stonehenge. It was hidden for 4,000 years buried under a mound of earth.

What's phenomenal about Newgrange is that it is aligned to the winter solstice. So that for a few days either side of the shortest day and longest night of the year, a ray of light from the rising sun enters through the roofbox and flows into the 19-metre passageway until it reaches the back of the body-shaped cruciform chamber. There, it softly illuminates a white carved basin stone and the famous orthostat with the triple spiral.

The lightshow lasts 17 minutes.

The solstice marks the seasonal turning point from the death of winter and the natural world, to a return to life with the promise of longer days.

In Newgrange, the masculine sun enters the vulva of the goddess penetrating the birth canal with light until it reaches her womb. There, the dreaming remains of our ancestors would have been regenerated with the life of the sun. The goddess’s tomb womb an intermediary between life and death.

"For the rest of the year the interior of the temple was in darkness. The ritual enacted must have been one of the sun fertilizing the ‘body’ of the earth and so awakening her after her winter sleep to the renewed cycle of life."

-Anne Baring & Jules Cashford

Milky Goddess

Bóinn by Jim Fitzpatrick

Irish astronomer and journalist Anthony Murphy of Mythical Ireland points out how Newgrange’s land, Brú na Bóinne in Gaeilge, is most often interpreted as Brú ("Brew") meaning 'palace' or 'mansion', but it can also mean ‘belly’ or ‘womb’ in Old Irish.

Bóinne (“Boy-nyah") derives from the River Boyne whose banks Newgrange rests into. The river is named after the Goddess Bóinn ("Bow-in"). The river is the goddess.

Bóinn’s name means ‘White Cow’, Bó Fhionn. So in this way, Newgrange could mean the ‘Womb of the White Cow’.

Indeed, Bóinn’s lover the Dagda (“Dawg-da”), the father figure of Ireland’s supernatural race, the Tuatha Dé Danann, and their son, the love god, Óengus (“Aengus”) are said to reside there.

The Irish for Milky Way is Bealach na Bó Finne – the ‘Way of the White Cow’.

This gifts us divine symbolism to work with at this time of year. To release our dreams into the cosmos and nourish them in the milky breast of the goddess Bóinn.

"The flowing breast is the essential image of trust in the universe. Even the faintest pattern of stars was once seen as iridescent drops of milk streaming from the breast of the Mother Goddess: the galaxy that came to be called the Milky Way."

-Anne Baring & Jules Cashford

And so, hear the voice of Goddess Bóinn ask you now:

What holy longing calls to you?

What is dreaming through you?

Can you gift these cherished dreams of yours to Bóinn to bathe in her milky bath of stars?

And enter 2023, feeling this numinous connection to your mythical lineage. To feel supported in and nourished by the milky breast of the goddess.

Unearthing the Goddess in Leadership

Mythic images have a tremendous impact on our cultural psyche. The cult of the warrior has filtrated down through time into modern leadership. To lead from the feminine we have to be able to dream, to imagine from a feminine place.

‘Nyx’ by Amanda Clark

For the past while, I’ve been stewing and swirling in the design of the Sovereignty Goddess Incubator. For me, a critical component of this programme is to explore how the earliest human cultures worshipped the godhead as the Great Mother who through sacred union would become an expression of both divine feminine and divine masculine.

One of the greatest travesties of the evolution of western monoculture is that we are missing the image of the mythical feminine in our collective consciousness. For many, she remains only in the memory of the collective UNconsciousness.

In Ireland for over a thousand years now, the overculture has seen and placed value on God or masculine, without Goddess or feminine.

‘Psyche and Cupid’ by Elihu Vedder, 1836–1923

The dangers of this cannot be understated as this affects how we lead in our work, our communities, our national arenas, and our global collective.

Mythic images have a tremendous impact on our cultural psyche. To lead from the feminine we have to be able to dream, to imagine from a feminine place. We have to see her image in nature, in the cosmos, and most crucially within ourselves and our own bodies. We have to speak to her and allow her to speak to us without fear of perceived insanity.

The reality is, I simply cannot be a feminine leader without her.

‘Cuchulain in Battle’ by J.C. Leyendecker, 1911

Despite our having so many rich stories of goddesses, the prevalent mythic image in Ireland has been the male hero warrior. In Irish children’s books, in Irish schools, the person who everyone knows is Cú Chulainn (Hound of Culann) - the almighty, all-conquering, lone hero who’ll sever your head if you look at him sideways.

I say this in jest but the cult of the warrior has filtrated down through time into modern leadership. There are always exceptions but for the most part, traditional leadership has been hierarchical, individualistic, top-down decision-making, focused on the gain of the few, making sacrifices at the expense of others (usually the vulnerable) in order to win because the end always justifies the means.

And yet long before Christian monks recorded the exploits of Cú Chulainn, our ancestors built great megaliths in honour of the goddess, the Great Mother. Monuments like Newgrange attest to this. A tomb womb which for most of the year lies in darkness until the winter solstice when it is fertilized by the light of the rising sun regenerating the sleeping remains of the forbearers and waking the goddess from slumber so as to bring new life with the promise of longer days.

It was from the cosmic womb of the goddess that we were birthed and it was back to her we went after we died in an eternal regenerative cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth.

And so, the mythos of the feminine as divine Creatrix, as leader of the community must be reclaimed if we are to infuse and disrupt dominant leadership models with feminine values.