MUSINGS FROM THE OTHERWORLD

My current writings and musings on Celtic feminine mysticism and soulful living now find their home on Substack. I invite you to join me there but I’ve also preserved an archive of my previous writings (2021-2023) below.

A Dream of Sinéad

Sinéad never went into the shop of my dream in fact, she was always the one pulling us out of it. Some of us would falter like a lost sheep and wander back in, and she’d pull us out again. But she did much more than that, she sought to demolish the shop altogether.

Faith by Jeanie Tomanek

My dreamworld and all that surfaces from its abyssal waters is one, if not the, most crucial guides in my life. Dreams rolled in like a thick foggy presence since early childhood. A density that for a long time seemed more curse than blessing. My dreams are my truthtellers showing me the truth of my life through symbols. Symbols that I then have to spend time deciphering. My dreams force me to do the work.

As many of you will know, the dreamscape is something I incorporate into my work as like the Otherworld, dreams can emerge from the sea of the collective unconscious. I go back to university in Ireland this September to study dream more intensely with Jungian psychology and art therapy. I rarely share a dream before working with it – be that through writing, drawing, art, making, imaginal journeying, moving as the dream, or exploring it through analysis. This takes time and I like to metabolise before sharing if at all. But today, I share a dream with you I had last Friday night.

I share it because it featured Sinéad O’Connor, our beloved Banríon who passed away last week. It is a sorrow-stricken and painful time in Ireland as we honour Sinéad who used her voice and art to fight so courageously to expose the horrors of Irish society. She did so with relentless soul, understanding inherently that without the nigredo, we can have no alchemy, we can’t transform. And Ireland desperately needed and still needs to transform.

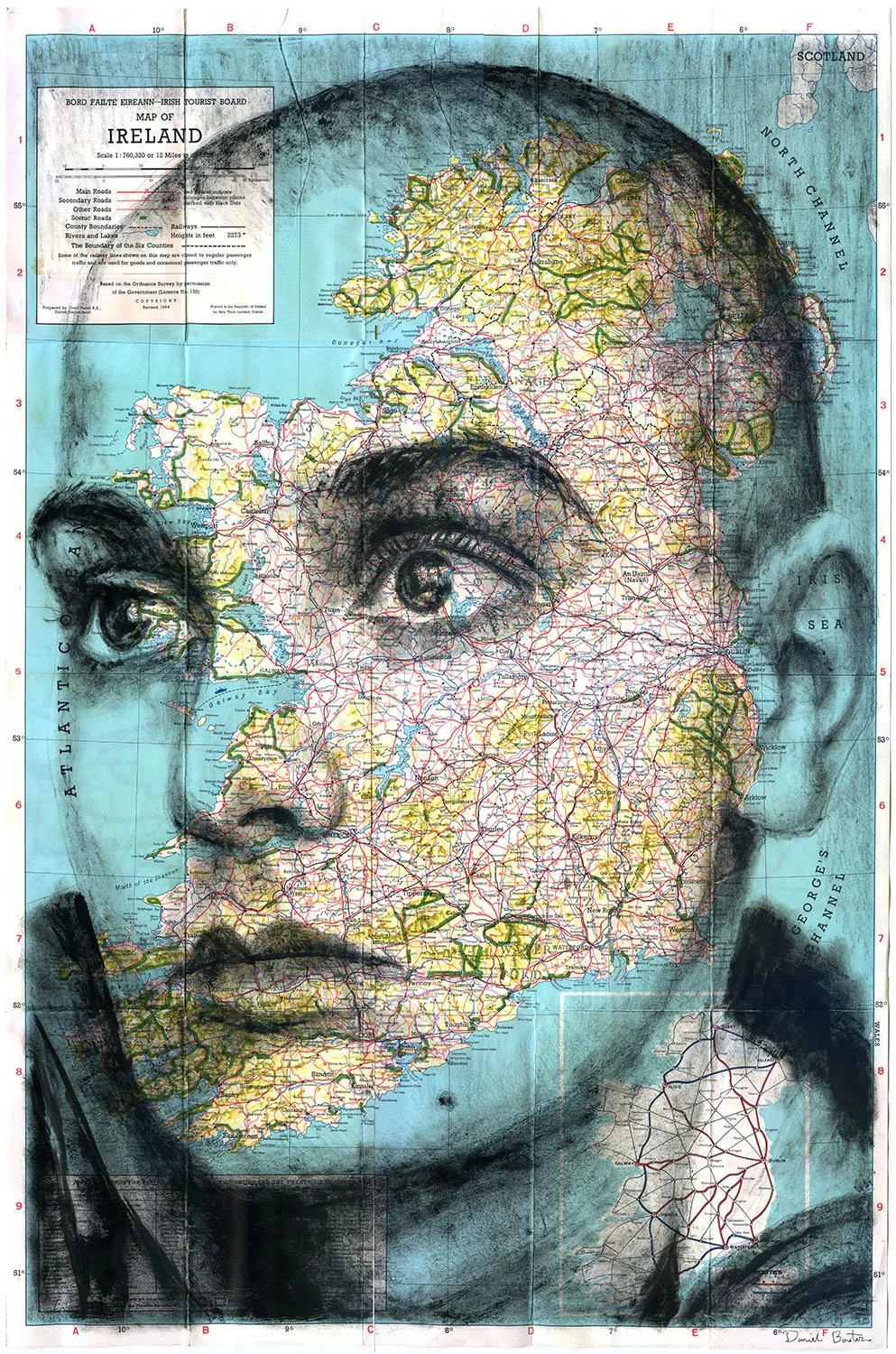

Sinéad O’Connor by Daniel Baxter

So the dream goes…

‘In the dream, I was creating three huge sculptures of Sinéad O’Connor’s head and shoulders. The first sculpture of Sinéad was silver, the second was gold, the third was red-gold. These were positioned high on a hill. When I came back down to the foot of the hill, I saw a huge shopfront there. Its glass was clear and encased in lovely sage green wood. It looked like a bookshop. When I looked through the glass, I saw that the shop was split into two levels. There was a ground floor and an upper floor. The left side of the shop on both levels was filled with hundreds of women who were dressed like Little Bo-Beep from the nursery rhyme. When I looked to the right side of the shop, on both levels I saw hundreds of men wearing suits. The Suits were speaking tyrannously at the Little Bo-Beeps who mumbled passively and laughed nervously in response. I then noticed a big “Closed” sign on the door and the dream voice said to me, “You can never go in there again.” I wake up.’

I will brew in the broth of this dream but there are bubbles boiling to the surface. The creation of the sculptures of Sinéad positioned high on the hill are symbolic of her being a personal icon and particularly during my formative years in the grimness of 1990s Ireland. I went to the same secondary school as Sinéad did for a time years after her, and so, she was in ways, a school symbol for the rebel many of us longed to be and tried to express. Some time ago I was asked to create a vision board of my feminist heroes and I printed, cut out and glued a picture of Sinéad front and centre, which felt symbolic as teenage me despite being awestruck by her had no real notion of the profundity of her courage.

I read in the Irish media recently,

‘Sinéad O'Connor was everything Official Ireland didn't want women to be, and we loved her for it.’

From ‘Troy’ by Sinéad O’Connor

The dream is oversimplified in terms of gender, we know the Little Bo-Beeps and Suits are not simply women and men. Yet, it shows a patriarchal presentation of ‘power over’ and the expectation of women and marginalised communities to be passive recipients of ‘authority’. In her life, Sinéad was consistent in questioning - who is the ‘authority’? Who holds the power? Who says so? How did they come to hold this privilege? Is this power over or power with?

I also feel a charge in that Little Bo-Beep is a maiden. As women, we often get locked in eternal maidenhood, in a prison where we can’t evolve into the Great Mother or crone of our lives. We’re not allowed to age, to evolve in wisdom. The scrutiny of women’s ageing is a form of cultural control and to a terrorising level for any woman in the spotlight like Sinéad. As Naomi Wolf said in the Beauty Myth:

‘The beauty myth is not about women at all. It is about men's institutions and institutional power.’

Sinéad O’Connor was never passive in her maiden expression. In her memoir, Rememberings, she shares the story of her decision to shave off her hair in response to her record label executive who:

‘…announced he’d like me to stop cutting my hair short and start dressing like a girl. He was disapproving of my recent attempt at a (very short) Mohawk. He said himself and Chris would like me to wear short skirts with boots and perhaps some feminine accessories such as earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and other noisy items one couldn’t possibly wear close to a microphone.’

After the deed was done, her head shaved in defiance, she says:

‘Me? I loved it. I looked like an alien. Looked like Star Trek. Didn’t matter what I wore now.’

Edra: Queen of Pentacles as the Great Mother by Barbara Walker

Sinéad never went into the shop of my dream in fact, she was always the one pulling us out of it. Some of us would falter like a lost sheep and wander back in, and she’d pull us out again. But she did much more than that, she sought to demolish the shop altogether.

Let me tell you, I’ve been the Little Bo-Beep many times in my life and I’ve also stood for long periods outside looking in with despair. I will never be as courageous as Sinéad O’Connor and I will be forever grateful to her for the permission she gave Mná na hÉireann to be our bold and brave selves. Because being on the outside can be terrifying.

I’ve often wondered when standing outside, what got me here? And it’s only recently that I’ve realised when all of the veils of illusion I hold finally burn away - if they ever do, it’s that part of me that’s left, the essence of my being, my soul that puts me there and like the dream voice says, “You can never go in there again.” It’s the part of me that lives through the belief that reclaiming and evolving the mythic feminine for our times is a powerful form of resistance and disruption from our patriarchal and capitalist overculture.

Like Sinéad, we have to use our creativity, our art, our diversity, and our voices to stand together in the truth of who we really are and who we are called to be. We have to give ourselves permission to evolve.

Together, we can demolish the shop so that all we see is Sinéad’s silver, gold and red-gold wonder shining down on us and perhaps giving us a wink of approval, or three! ❤️

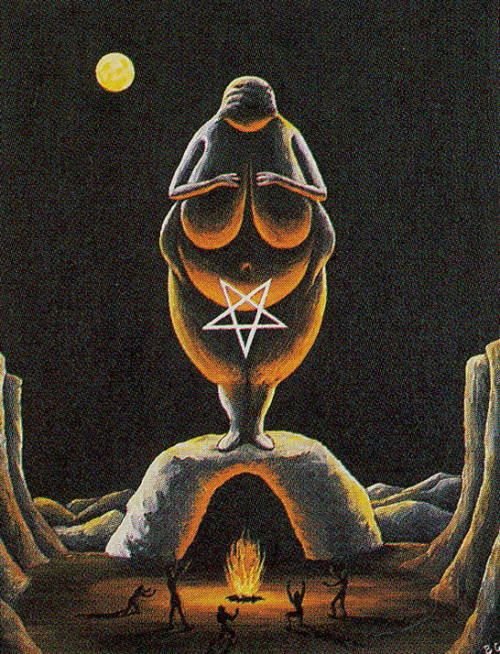

The Hell Fire Club. Source Viator.

A song that I have been moving, shaking, weeping to, and finding resilience within the past few days is Troy. This is my favourite Sinéad O’Connor song. It’s a masterpiece. And so, I wanted to share the video with you if you haven’t seen it or desire to revisit.

The building that explodes in the video is called the Hell Fire Club on Montpellier Hill, a haunt well known to most Dubliners as it peers in its eery eminence over our city. It was originally an old hunting lodge built by William Connolly in 1725. Following his death it became a club for wealthy Dublin men who dabbled in the dark arts. The devil himself with his cloven hooves is said to have been a frequenter of the Hell Fire Club. In 2016, archaeologists discovered a 5,000-year-old passage tomb on the site. It was long held in folk memory that stones from the ancient cairn was used to build the club itself, which resulted in all kinds of supernatural happenings.

It’s a symbolic video on so many levels. FEEL the feminine, the Great Mother, Sinéad O’Connor, roar.